by John Hill

This summer, one of our agents was hired to represent the buyer in a raw land deal. A contract was struck and a feasibility period began to pin down the development cost the city would require if this property was rezoned for residential use.

The contract was extended multiple times due to a difference in interpretation of city code between the buyer and city of Abilene planning staff. For the agricultural open space (AO) to be rezoned for residential development, the developer read city code to require the rebuild of 400 linear feet of the collector street that served the entry of the proposed project. Staff at the City of Abilene said the rezone required the rebuild of a 1.15 mile stretch of road before the zoning change would be granted. The wide difference in cost between these two interpretations led to repeat meetings with city staff, delayed closing with multiple amendments and threatened to kill the deal.

Since my days on city council, I’ve heard individuals tell stories about disagreements between planning staff and business owners/developers. Some local developers and business owners conclude: “Abilene is a difficult town to do business because of our planning staff”. Certainly, no successful city needs this perception.

I also recognize that perception has to be considered in context. Perhaps a developer’s experience with the city’s planning department is more like a university parking problem. I’ve attended, taught at or been a trustee for a total of 8 colleges. Enrollment at these institutions range from 1,700 to 35,000. Location runs the gamut from downtown Dallas to rural Tennessee. All are unified by the relative perception that parking is awful and MUST be fixed.

THE DATA

Using 5,901 NTREIS-archived transactions going back to January 2009 on commercial property and raw land sales, I attempt to measure the perception that Abilene is unfriendly to business. Each transaction includes the date when the sales contract was inked and the date when the property ultimately sold – what I’ll call contract-to-close time. The difference between these dates is explained, in part, by due diligence that may involve conversations with local city planners. If the planning process is contentious, this number grows as commercial property or raw land lingers under contract without a consummated sale.

It would be interesting to know the back story behind the listings beyond the 5,901 used in this study that never reached the closing table. NTREIS archives expired listings and it would be helpful to know if these listings expired because of unresolved planning concerns, an unreasonably ambitious seller or weak market conditions. By focusing on consummated sales we remove the latter issues as we attempt to close in on the role of the planning process and its influence on completed deals.

This information was entabled for 90 cities in the NTREIS region. The average days between contract and close by city reveals that it takes 43 days or roughly a month and half between contract and close date. Abilene contract-to-close time for Abilene is 42 days – one day under the mean. In the context of other cities for which NTREIS maintains data, we are average.

This table also summarizes variables by city that help explain contract-to-close time. These variables were used to calculate:

- The percent change in population between 2010 to 2015. The idea is that faster growing towns have “growing pains” which lead to delays in closing real estate deals.

- The average value of residential structures. This is tabulated by averaging the total value of 2015 permits by the number of permits issued in 2015. Towns with expensive properties have more at stake in development and, therefore, spend more time on the market.

- % Difference in mean v. median income: this is a proxy for community homogeneity. Eastland has the widest difference at .45% which indicates you have disparity between the haves and the have-nots. Aledo and Dublin at 97%=median/mean indicates little difference between mean and median, signaling a more homogeneous town in terms of household income. Interestingly, these two extreme have some of the lowest contract-to-close time. It’s my notion that income homogeneity brings accord to the planning process and the wishes of the public and helps the process move faster. Likewise, a dominant income overclass understands how to facilitate land use with little protest from individuals with less of an economic stake and the city that relies on their leadership falls in line.

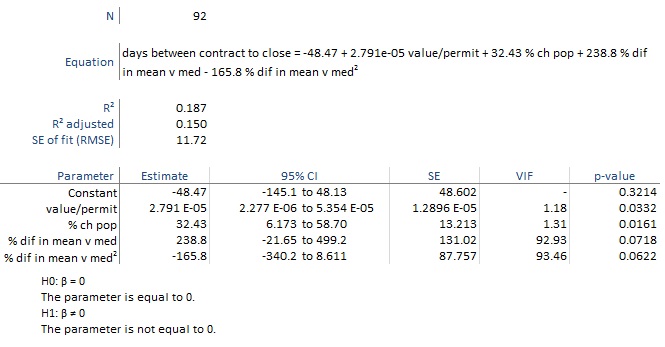

THE MODEL

A linear regression of these three variables was tabulated. A fourth variable: the square of the % difference in mean income v. median income was also added to account for the similarity in contract-to-close time between homogenous and heterogeneous local incomes.

To interpret, ceteris paribus:

Every $100,000 gain in value adds 2.79 ≈ 3 extra days to contract-to-close time. (statistically significant at 97% level of confidence)

Every 3% gain in population adds .97 ≈ 1 day to contract-to-close time (statistically significant at 98% level of confidence)

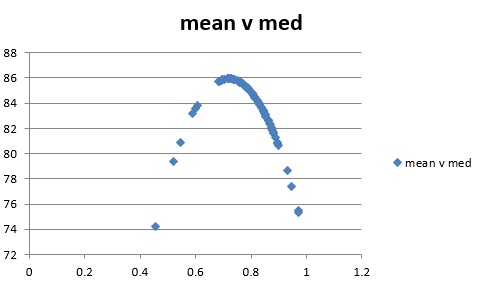

The percent difference in median v. mean income is explained using the following graph.

It explains that towns with separation in incomes like Commerce at 54.51% median v. mean income ($41,758 median income / $60,332 average income) are roughly identical in contract-to-close time when compared to towns that are more economically homogeneous like Roanoke at 89.52% median v. mean income ($61,010 median income / $68,150 mean income). To calculate:

Predicted contract-to-close for Roanoke: 80.58 days = 89.52% x 238.8-165.8 x 89.52%^2

Predicted contract-to-close for Commerce: 80.88 days = 54.51% x 238.8-165.8 x 54.51%^2

According to the model, towns like Granbury should fair the worst. Their median v. mean income measure is is 72.42%. This mix of mean versus median incomes is the worst for generating a favorable climate to accelerate the contract-to-close process. For them:

Predicted contract-to-close for Granbury: 85.94 days = 72.42% x 238.8-165.8 x 72.42%^2

or roughly 5 extra days to close when compared to Commerce and Roanoke. Median-to-mean income for Abilene is marginally better than Granbury. For us:

Predicted contract-to-close for Abilene: 85.73 days = 75.56% x 238.8-165.8 x 75.56%^2

While the role of mean v. median income plays an interesting role in explaining contract-to-close timing, it is important to remember this is only one factor. Abilene homes are cheaper than many cities in this study and our population certainly grows slower – these both improve contract-to-close time. While our constant in the econometric model is insignificant (indicating we’ve found variables that successfully explain contract-to-close time), the model has a adjusted R-squared of .15 telling us that only 15% of the variation in this data is explained by this model.

CONCLUSION

Planning offices arbitrate externalities posed by disparate plans for land use. When the financial stakes are low, population growth moribund and the population is either dominated by an income overlord or possesses similar incomes and land use perspectives, contract-to-close time is reduced. On the other hand, explosive population, expensive homes and a balance of haves and have-nots create the right situation for a fight that drags out real estate deals.

I’m not saying Abilene is perfect, but if one chooses to accept contract-to-close time as a legitimate yardstick of how our planning process assist real estate deals, we aren’t bad, either.

Leave a Reply